Green's theorem examples

Example 1

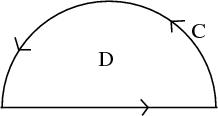

Compute \begin{align*} \oint_\dlc y^2 dx + 3xy dy \end{align*} where $\dlc$ is the CCW-oriented boundary of upper-half unit disk $\dlr$.

Solution: The vector field in the above integral is $\dlvf(x,y)= (y^2, 3xy)$. We could compute the line integral directly (see below). But, we can compute this integral more easily using Green's theorem to convert the line integral into a double integral. The integrand of the double integral must be \begin{align*} \pdiff{\dlvfc_2}{x} -\pdiff{\dlvfc_1}{y} = 3y -2y = y . \end{align*}

Since the line integral was over the boundary of the half disk, the region of integration for the double integral is the half-disk $\dlr$ itself. (Since $\dlc$ was oriented counterclockwise, the orientation matches; otherwise, we would have had to multiple by negative one to get the correct sign.) The region $\dlr$ is described by \begin{align*} -1 \le x \le 1,\\ 0 \le y \le \sqrt{1-x^2}. \end{align*} Therefore, by Green's theorem, \begin{align*} \oint_\dlc y^2 dx + 3xy\, dy & = \iint_\dlr \left(\pdiff{\dlvfc_2}{x} -\pdiff{\dlvfc_1}{y}\right)dA\\ &= \iint_\dlr y dA\\ &= \int_{-1}^1 \int_0^{\sqrt{1-x^2}} y\, dy \, dx\\ &= \int_{-1}^1 \left( \left.\frac{y^2}{2} \right|_{y=0}^{y=\sqrt{1-x^2}}\right) dx\\ &= \int_{-1}^1 \frac{1-x^2}{2} dx\\ &= \frac{x}{2} - \left.\left.\frac{x^3}{6} \right|_{-1}^1\right. = \frac{2}{3}. \end{align*}

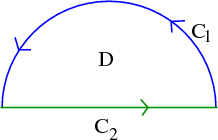

Alternative Solution method: You could also compute this line integral directly without using Green's theorem, and you better get the same answer. However, in this case, the integral is more difficult.

We have to compute the integral in two pieces. The first piece is the half circle, oriented from right to left (labeled $\dlc_1$ and in blue, below). The second piece is the line segment, oriented from left to right (labeled $\dlc_2$ and in green).

First, calculate the integral alone $\dlc_1$. Parametrize $\dlc_1$ by $\dllp(t)=(\cos t, \sin t)$, $0 \le t \le \pi$. Then $\dllp'(t) = (-\sin t, \cos t)$. Calculating: \begin{align*} \lint{\dlc_1}{\dlvf} &= \plint{0}{\pi}{\dlvf}{\dllp}\\ &= \int_0^\pi \dlvf(\cos t, \sin t) \cdot (-\sin t, \cos t) dt\\ &= \int_0^\pi (\sin^2 t, 3 \cos t \sin t) \cdot (-\sin t, \cos t) dt\\ &= \int_0^\pi (-\sin^3t + 3 \sin t\cos^2 t ) dt\\ &= \int_0^\pi (-\sin t(1-\cos^2 t) + 3 \sin t \cos^2 t ) dt\\ &= \int_0^\pi (-\sin t + 4\sin t \cos^2 t ) dt \end{align*} We can calculate that \begin{align*} \int_0^\pi \sin t \, dt = 2 \end{align*} and (let $u=\cos t$, $du = -\sin t \, dt$) \begin{align*} \int_0^\pi \sin t \cos^2 t\, dt &= \int_1^{-1} - u^2 du\\ &=\left.\left. - \frac{u^3}{3} \right|_1^{-1}\right. = -(-1)/3 + 1/3 = 2/3. \end{align*} Therefore. \begin{align*} \lint{\dlc_1}{\dlvf} = -2 + 4(2/3) = -2 + 8/3 = 2/3. \end{align*}

The integral along $\dlc_2$ is easy. Along $\dlc_2$, $y=0$, so that $\dlvf(x,y) = (y^2,3xy) = (0,0)$. Consequently, \begin{align*} \lint{\dlc_2}{\dlvf} = 0. \end{align*}

Putting this all together, we verify that \begin{align*} \dlint = \lint{\dlc_1}{\dlvf} +\lint{\dlc_2}{\dlvf} = \frac{2}{3} + 0 = \frac{2}{3}. \end{align*} Our direct calculation of the line integral agrees with the above result that we obtained by applying Green's theorem to convert the line integral to a double integral.

Example 2

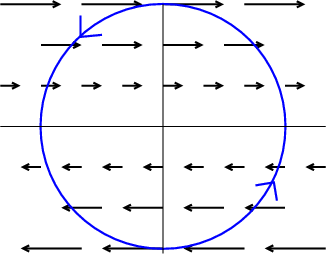

Let $\dlvf=(y,0)$. What is sign of the circulation of $\dlvf$ around the CCW-oriented unit circle? Calculate circulation exactly with Green's theorem where $\dlr$ is unit disk.

Solution: The circulation of a vector field around a curve is equal to the line integral of the vector field around the curve. We can see from the picture that the sign of circulation is negative, as the vector field tends to point in the opposite direction of the curve's orientation.

Since we must use Green's theorem and the original integral was a line integral, this means we must covert the integral into a double integral. The requisite partial derivatives are \begin{align*} \pdiff{\dlvfc_2}{x} = 0, \quad \pdiff{\dlvfc_1}{y} = 1, \quad \pdiff{\dlvfc_2}{x} - \pdiff{\dlvfc_1}{y} =-1, \end{align*} so that original line integral becomes the double integral \begin{align*} \dlint &= \iint_\dlr (-1) dA\\ &= - \iint_\dlr dA. \end{align*} Now, we could go ahead and compute this double integral. But we are lazy. We know that the above integral is simply the area of $\dlr$. So, we take the shortcut: \begin{align*} \dlint &= - \iint_\dlr dA\\ &= -1 \cdot \text{area of } ~ \dlr = -\pi. \end{align*} At least our answer is negative like we concluded it must be.

Thread navigation

Multivariable calculus

Math 2374

Notation systems

Similar pages

- The idea behind Green's theorem

- When Green's theorem applies

- Other ways of writing Green's theorem

- Green's theorem with multiple boundary components

- Using Green's theorem to find area

- Calculating the formula for circulation per unit area

- A path-dependent vector field with zero curl

- The fundamental theorems of vector calculus

- More similar pages